Greek Runners - Photo: Hans Giessen

What is the story behind the myth of the marathon? Michel Bréal, Plutarch, Herakleïdes, and Herodotus – Prof. Hans Giessen

Michel Bréal, a French university professor of German origin who was a friend of Pierre de Coubertin, is considered to be the inventor of Marathon as a sport:

He suggested to Coubertin, who was organizing the first Olympic Games in Athens in 1896, that a race from Marathon to Athens be organized, “then we would have a link to antiquity.” But what do we really know about marathon running – or marathon races? – in antiquity?

The first marathon in history probably took place in the midsummer of 490 BC: the Athenians had repelled the great Persian army in the plains of Marathon, about 40 kilometers from Athens; a messenger then ran from Marathon to Athens to deliver the good news.

The oldest known description of the first marathon comes from Plutarch. In his short work De Gloria Atheniensium, he writes:

According to the historian Heracleides Ponticus, the news of the Battle of Marathon was conveyed by Thersippos from Eroiadès; however, according to the most widely held view, it was Eukles who, still in full battle gear and sweating from the fight, ran off, reached the entrance to the council building with his last ounce of strength, and could only shout: ‚Rejoice!‘ and ‚We have won!’ – and died immediately afterwards.“

What is true about this story? Indeed, if the story is true, the runner (whether it was Euklès or Thersippos) died as a result of excessive exertion. But he was able to report an impressive success: the citizens of the two small towns of Athens and Plataiai had put the army of the great Persian Empire to flight. This was quite remarkable: a small force had actually managed to repel the huge Persian army that had landed at the Bay of Marathon to conquer Greece!

The Persian fleet is said to have consisted of around 600 warships, plus horse transport ships carrying some 1,200 animals, all in all almost 100,000 soldiers (and a total of around half a million people!), as listed by the Greek historian Herodotus. These figures are probably exaggerated. But the Persians‘ superiority was undoubtedly overwhelming. First, they demanded that the Greek poleis offer them earth and water. Some communities accepted fearfully, such as Aegina, the island off Athens in the Saronic Gulf. But Athens itself, Sparta, and several other communities, such as Eretria, refused.

Of course, the Persians accepted this challenge. In the summer of 490, they landed on the plain of Marathon. The name “Marathon” means “fennel field.” The plain of Marathon is located on the east coast of the Attica peninsula; the city of Athens is located on the west coast — so the landing site was too far away to be well secured, but close enough for the attackers to reach the city of Athens quickly.

Athenian observers must have watched the landing. It must have been impressive! Apparently, it was part of the Persian strategy to demonstrate to the Athenians how large and well-equipped the advancing forces were! Perhaps many citizens would be discouraged, want to avoid battle, and defect to escape punishment after the foreseeable defeat?

The bust of Michel Bréal – Photo: Hans Giessen

The popular assembly met in Athens. A commander named Miltiades argued particularly aggressively and was able to convince the Athenians not to entrench themselves behind the city walls, but to take up the fight. Probably just under 10,000 Athenians and around 1,000 citizens from Plataiai moved to the east coast and set up their army camp on the southern edge of the plain, where they could block the Persians‘ direct route to Athens. That was all there was; above all, there was initially no support from other Greek cities. The Athenians sent a messenger to Sparta with a request for help, but time was running out.

Apparently, Marathon had only been intended by the Persians as a base from which to negotiate – or attack. They were probably surprised that the Athenians left their city relatively unprotected and prepared for battle so far away from it. This was surprising, but also surprisingly effective, because now the Persians were tied to the plain of Marathon and could no longer operate as freely as they wanted.

So in the summer of 490, the two armies faced each other on the plain of Marathon and eyed each other up. The Persians were apparently waiting to see if the Athenian defensive front would crumble after all. The Athenians waited because they were counting on help – enough time had passed that the Spartans could arrive soon. It was a bit like a game of chess: usually, the one who keeps up the pressure wins. On the other hand, those who constantly have to reorient themselves and react to attacks with their defense cannot develop their own strategy. Normally, the Persians were the attackers. The surprising move by the Athenians to leave their home city and march toward Marathon had at least changed that.

On the plain of Marathon, the Persians were condemned to virtual immobility. They had no choice but to try to regain the initiative. It can therefore be assumed that the next move — the first movement after days of standstill — came from the Persians. The Athenians quickly realized that movement had come to the deadlocked situation. All historians agree that they had only a small window of opportunity, so they made a quick sacrifice, put on their armor, and rushed off. The Persians as well as the Greeks reached the ships. There was fierce fighting. The Persians retreated.

This ended the fighting on the plain of Marathon. This was the moment of the Marathon Run described by Plutarch.

Did this Marathon Run actually take place? Plutarch, who lived 500 years later, refers to Heracleides Ponticus, apparently an authority on the subject. However, we do not know what Heracleides, who lived from around 390 to 310 BC (still more than a hundred years after the event described), actually reported – his account has been lost. Since Herodotus, who lived closer to the time, did not mention the marathon, it has occasionally been suggested that Plutarch (or Heracleides) may have invented the event.

Herodotus of Halicarnassus was born between 490 and 480 BC – shortly after the Battle of Marathon. Herodotus was known for conducting extensive research. He travelled around the world and interviewed all the decision-makers from the time of the Persian Wars who were still alive and whom he could reach. Then he began to write and recite what he had written. We don’t know exactly when the entire work was completed, only that it had definitely been published and was widely known by 425.

The Bréal Cup – Photo: Hans Giessen

What is significant is that he was probably the first author to attempt to give all sides a voice – “I see it as my duty to report everything I hear – which does not mean, of course, that I have to believe all reports,” he wrote. He is thus considered the first critical reporter. He distinguished between occasion and cause and reflected on the motives behind the actions – all of which was completely new and unusual, and is still considered serious from today’s perspective.

Herodotus also describes the long run that a certain Pheidippides undertook from Athens to Sparta to request support, while the rest of the men marched to the plains of Marathon. Herodotus‘ account is credible and plausible. Every army had so-called running men; horses played no role in ancient Greece. Although it is around 250 kilometers from Athens to Sparta, and Pheidippides had to run almost non-stop for two days, there are examples that show this is possible: in 1982, British soldiers organized a run from Athens to Sparta, and since then a so-called Spartathlon has been held every year. Numerous competitors take on the ordeal, most of them complete it, and the fastest finish in well under 30 hours!

Furthermore, Herodotus does not mention that Pheidippides ran back again – at least not immediately. Apparently, he first recovered from his exertions in Sparta. But in principle, such a run is possible – and the political, military, and religious circumstances described are all the more credible and probable.

But the Spartans were in the midst of religious celebrations. So the Athenians were indeed on their own. Apparently, the Persians also knew that the Karneia festival was being celebrated in Sparta at the time. Incidentally, the Karneia festival also allows us to date the Battle of Marathon. When Pheidippides arrived in Sparta, there were still six days until the full moon. After the full moon night, the Spartans set off immediately, but arrived at the battlefield too late. Herodotus describes exactly how long it took the Spartans to reach Marathon and how late they arrived. All one would need to know is the date of the festival to determine the exact day of the battle (and thus also the first actual marathon race). As early as 1855, a German researcher named August Boeckh calculated that the Battle of Marathon must have taken place on September 12, 490 BC. However, there are doubts about this date, as it has been shown that not all Greek cities used the same lunar calendar; Boeckh had based his calculation on the calendar of Athens, which he was familiar with. Perhaps the Spartans celebrated the festival a month earlier, in which case the Battle of Marathon would have taken place on August 15, 490.

But even if Herodotus did not mention the Marathon Run itself, it seems unlikely that it was a pure invention. Those who write in the time when developments happened do not need to describe things that are self-evident to the contemporaries because they are obvious and inevitable to them. It indeed seems reasonable to assume that the Greeks routinely sent a messenger after a battle to inform about the outcome to those who had stayed at home. Families had to be informed quickly, not least so that they could flee in time in the event of defeat. It is therefore highly probable that a messenger was sent from Marathon to Athens – and equally probable that he covered the distance as quickly as possible. Incidentally, Herodotus confirmed that there were runners at that time who could cover much longer distances quickly with his story of Pheidippides.

We can therefore assume that Plutarch’s statement is correct and that the first marathon in history almost certainly took place in the midsummer of 490 BC, either on August 15 or September 12.

And what about the story of his dramatic death?

It seems certain, at least, that Plutarch’s version is based on a legend that was widely known at the time – and did not spring from the author’s imagination. Plutarch’s rather casual style is the main argument against it being a fabrication. If he had wanted to tell a surprising, newly invented, and fascinating anecdote, he would have had to build up the punchline differently. It can therefore be assumed that the story of the death of Euklès or Thersippos was common knowledge 500 years after the event.

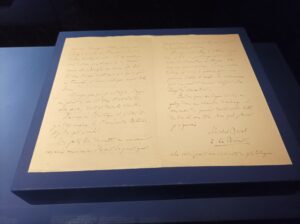

The letter from Bréal to Coubertin – Photo: Hans Giessen

However, the fact that a story is common knowledge does not necessarily mean that it is true or plausible. As impressive as the story of the runner’s dramatic end sounds, it is not very likely. There is much to suggest that it was added later. Shortly after the Persian Wars, it was not yet known. If it had a basis in reality, this story would have been described in detail by Herodotus, among others; he never missed a good anecdote. It would not have been a matter of course (such as a runner delivering news of the course of the battle to those who had stayed at home), but rather a highly existential human interest tragedy. The fact that Herodotus does not tell it means with great certainty that it did not happen.

Especially since the story itself is not very plausible. What is particularly implausible is that the runner is said to have run the distance from Marathon to Athens in full battle gear. Such gear is not light. Even today’s world-class runners, who train specifically for long-distance running, would have difficulty running the distance in combat gear made of heavy leather and steel. It would undoubtedly have taken little time to take off the gear and rush to Athens lightly clothed – significantly less time than was probably lost by running in heavy clothing. Of course, the battle gear explains the runner’s total exhaustion; it is therefore necessary to make his dramatic death seem plausible. But it could only appear credible after people no longer had any experience with messenger runners. And even then, the idea that the messenger sprinted in full gear is irritating.

Therefore, there is a further assumption that the Athenians developed commemorative rituals for the Battle of Marathon in later years. This may have included a commemorative run, which was then carried out in military clothing for symbolic reasons. Presumably, however, there was initially only one runner who set off as part of the commemorative celebrations, and no race yet.

Michel Bréal invented marathon running as a sport, albeit against the backdrop of his academic knowledge of Greek history. In his letter to Coubertin, Bréal wrote that he himself wanted to donate a trophy for the winner, thus ending his letter.

Coubertin was thrilled! In the program for the first Olympic Games, the marathon even appeared as a completely separate category, independent of the other running and athletics competitions: “Running competition, called the marathon, over a distance of 48 kilometers from Marathon to Athens, for the trophy donated by Monsieur Michel Bréal, member of the Institut de France.”

Why 48 kilometers? This was obviously Coubertin’s initial rough estimate. An exact length was not specified at first. In fact, there were two routes that the historical runner could have taken: the direct route from Marathon to Athens, which led over the mountains and was therefore very strenuous, but only measured 35 kilometers. Or the route along the coast, which was slightly longer at 40 kilometers, but faster to run.

It is unknown which route the historical Marathon runner took. But for the first Olympic Games, the coastal route was chosen. So it came to pass that the first marathon was about 40 kilometers long. The distance of 42.195 kilometers only became standard with the 1908 Olympic Games in London – but that’s another story.

Shortly before the Olympic Games, the first test and qualifying runs took place. The first marathon of the modern era took place on March 10, 1896.

The marathon at the first Olympic Games was a great success: the king himself ran the last few meters, and to the delight of the audience at the time, it was a Greek, Spiridon Louis, who won and received Michel Bréal’s trophy.

And a new myth was born.

Prof. Hans Giessen

October 3, 2024: Exactly one year ago, the Bréal Marathon took place in Landau. Prof. Hans Giessen

.

EN

EN