2016 Toronto Marathon Toronto, Canada October 16, 2016 Photo: Victah Sailer@PhotoRun Victah1111@aol.com 631-291-3409 www.photorun.NET

THE EXTRAORDINARY MR WHITLOCK – Globe Runner blog » Butcher’s Blog – Articles by Pat Butcher

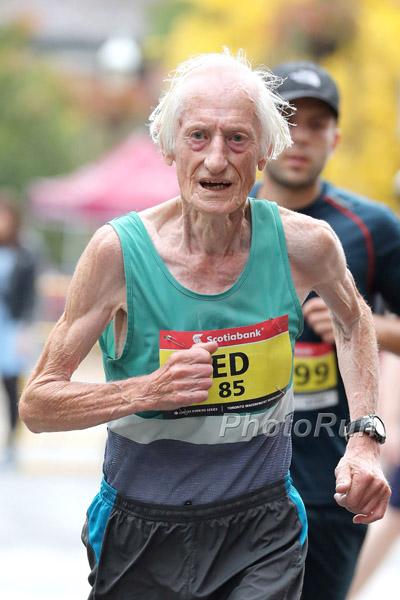

When Whitlock was only 73, he ran 2.54.48, making him the fastest and thus far only person in history over the age of 70 to run under three hours for the marathon. Around that time, he also ran well under 20mins and 40mins for 5/10k, something that should particularly resonate with the burgeoning parkrun com

nity. In addition, over the last twenty years he has set three dozen age-group world best times for both track and road races. To get a clearer idea of how this stacks up, there is something in athletics called age-grading where any performance can be measured against the mean. Whitlock’s 2.54.48 at 73 is the equivalent of 2.03.57 for an elite runner, which would have been a world marathon record through to 2011.

As a long-time athletics writer and occasional septuagenarian 5k runner myself (who struggles to break 25mins), I’d often pondered getting in touch with Whitlock, and having a chat. When I finally got round to it, via an introduction from another British born Canuck colleague and runner, Whitlock replied straightaway to say he was visiting the UK soon, and was happy to meet up. I raced to accept the offer; which is what found us chewing the fat in a greasy spoon on London’s South Bank recently, shortly after Whitlock arrived in Surbiton, Surrey on one of his occasional visits to see his sister.

Whitlock was born not far away, in Tolworth in 1931. He was a successful schoolboy runner (see photo below) in the late 1940s, a contemporary of the celebrated British Olympians, Gordon Pirie and Chris Chataway, He and Chataway were club mates at Walton Athletic Club, and they had an unusually illustrious colleague in the pioneer in Artificial Intelligence, Alan Turing, who got close to selection for the British Olympic team for Wembley 1948, when he finished fifth in the AAA Marathon earlier that year. “I got to know Alan quite well,” he tells me, “but nobody at the club had the faintest idea about all this gay stuff. That only came out much later”. (In one of the most disgraceful episodes in British social history, Turing was forced to take neutering drugs, which contributed to his suicide in the early 1950s).

Through the athletics club, Whitlock and his father got tickets every day for the Olympic athletics at Wembley, and his most vivid memory remains the 10,000 metres, “Heino (Viljo, of Finland) went straight into the lead, and being the world record holder, we thought that was that, but then (Emil) Zátopek took over, and went further and further away, and Heino dropped out. That was it, all over”. At this point, aged 17, Whitlock was still trading strides on an equal footing with Chataway and Pirie. But their paths diverged when he went to university, and concentrated on his mining degree while Pirie and Chataway were respectively donning army boots for hard cross country runs and hotfooting around cinder tracks in pursuit of their eventual medals and world records.

As Whitlock acknowledges, doing a degree in mining in early 1950s Britain was virtually an application for emigration, as well as a body-swerve of national service. “As we approached graduation, we had a visit from an army recruitment officer,” he relates with some amusement over sixty years later. “He told us what a grand time we’d have in army, we’d all be officers, etc, etc. The first question when he finished his diatribe was what happens if you leave the country. The conversation went downhill from there. Of 30 guys on my course at Imperial College, 28 left the country”.

Emigrating was a lot easier back then, this was the era of the £10 trip to Australia. Off the back of an application to a Canadian mining company in mid-summer 1952, Whitlock was on a boat to Montreal within the week, took a train to Toronto, and was down a nickel mine in Sudbury, north Ontario 24 hours later. “The Ontario Mining Association had this training scheme; you went and worked as a miner. I was in one mine for four months then two others, so a year’s training altogether. I spent four months at this nickel mine in Sudbury working as a miner, I did spend some time in the office; then I went up to a gold mine in Timmins. When I’d been there a while, they made me a job offer, testing drill bits and things. I stayed there for two, three years. There was no running there, in north Ontario. There was running in Toronto, but not in the north. I wasn’t motivated to be any sort of pioneer, my running back then was pretty mediocre, with my lack of results at university, so I just quit running”.

Having moved to Toronto, got married and raised a family in the interim, it was almost 20 years before Whitlock was tempted back into a tracksuit, and that, he says was “one happenstance after another. My wife went to my eldest son’s sports day. She got into conversation with some teenager who told her he was a runner; she said oh, my husband used to run, and he said my club’s looking for a coach. So she despatched me to this club….. I was sort of hanging around, and thought why don’t I jog around the track? I wasn’t dressed to run, but I had some footwear which was vaguely appropriate. These teenagers had never seen an old man running (he was 41). So I started training with them, doing some ‘intervals’. They’d entered a team for a provincial 4x1500m relay. One of the team got injured, so I was inveigled into running, and that was my first race in 20 years. I gradually got more and more into it, mainly middle distance running, but within a couple of years the club had died as an 800/1500 teenage team, and evolved into a long distance older runners club. So I was doing distance training in winter and track in summer. Off that training, I developed a decent amount of stamina”.

As Whitlock indicates above, there are two distinct types of training for long distance runners. One involves what is known as LSD, long steady distance, which came into vogue in the 1960s; the other, popularised by the immortal Emil Zátopek a decade earlier is interminable fast laps of the track, interspersed by short recuperative jogs, the whole known as ‘interval training’. Zátopek would do as many as 100 of these in a day. But Zátopek was the obsessives’ obsessive. Most track devotees do far fewer, and anyway, most distance runners use a combination of both systems, usually getting in a lot of long distance runs during the cross-country season in winter, before sharpening up with intervals on the track for the summer season. Whitlock has long recognised that LSD is his game, the more so since speed-work on the track is also a fast-track to injury; and his university career had been truncated by a bad Achilles’ tendon injury, which he says still flares up, should he ever be tempted back onto the tartan.

“I had no intention of running a marathon,” he continues, “but my youngest son, only 14, was hell-bent on running a marathon. He’d run every day for a year, and there was no ban on 14 year olds back then. He ran this marathon and I ran it with him, in Montreal in March ’76. There were snow banks on either side of the road, I ran it in full track suit, and we did 3.09; that was my first marathon (he had just turned 45 at this point). Then six weeks after we ran another one and did 2.58, then we ran another one the next year and did 2.52”.

But he was still fundamentally a middle distance runner, and in that guise got selected to run in the second World Masters’ (over 40s) Championships, in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1977. He was one of the favourites for the 800 and 1500 metres in the 45-49 years age group. He ran one minute, 59.9sec for 800, and just over 4.06 for 1500 metres. Believe me, these are superlative times, yet he could only finish third and second respectively, an indication of how veterans’ or masters’ competition was beginning to improve, as athletes extended their careers to hitherto uncharted age territory. In the next masters’ world champs two years later in Hannover, Germany, nearing the upper limit of that same age group, he finished fourth in the 800, but won the 1500 metres, in 4.09.6. That was also the year, 1979, when he ran his fastest marathon, in Ottawa, 2.31.23. At age 48!

His career was going full bore at this stage. “I was terribly ambitious in my 40s,” he tells me, “I’d get home from work, have my supper and then go out training at 10 o’clock at night. Then I’d have a shower and fall into bed, and that was it. But I got out of that in my fifties, I was too busy at work, and didn’t have time. I was basically doing two long runs at the weekend and no intervals at all. Nothing in midweek, just doing the occasional race. I didn’t really get going again until I retired, at 58. The company I was paper pushing for had some blood-letting, then I got a part-time job which suited me better, a company building a kiln, I had that for three years. I gradually got back into running. I didn’t work anymore after I was about 61, and I started to train a bit more, and ran a marathon here and there. I was running low 2.50s. Then I got to about 66, 67. I used to go and run a marathon in Columbus, Ohio which had decent prestige at that point, and I ran low 2.50s, 2.52, and I read that nobody had run a marathon under three hours in their seventies. All these people had run very good times, for example, the 66 year old world record was 2.40 or something like that, way under three hours”……

I will post the second part of this feature in a few days’ time

Pat Butchers

Posted on Sunday, January 1st, 2017 at 2:02 pm and is filed under Butcher's Blog | 0

In the interim, check elsewhere on this site for links to my latest book, QUICKSILVER, The Mercurial Emil Zátopek

EN

EN